Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities by Alain Bertaud is my favourite book on urban planning. In Chapter 6, Alain lays out a data driven approach to designing and evaluating housing policy. Here are a few ideas that have stuck with me.

Affordability: Household Incomes, Regulations, and Land Supply

Bertaud views cities as labour markets. Cities are full of incredible things, but without a functioning labour market there is no city. This means that people can find and change jobs whenever they want. Well functioning labour markets require affordable spaces to live. When people look for an affordable space, they make trade-offs between price, quality, size, and location to find the best option for themselves.

Housing is different than other commodities. If you can't afford airpods, you don't buy them. If you can't afford housing, you probably still have somewhere to live; it's likely just too small, too expensive, or too far away from work. In other words, your housing doesn't meet the socially accepted minimum housing standard. These standards are useful benchmarks, but they don't correspond to a scientifically accepted universal norm. What's socially acceptable is contextual and related to the standard in the city where they are applied.

The best housing options available to lower-income households often don't meet the minimum socially acceptable standard. One of the primary roles of government is to help these households. Governments feel pressure to provide affordable housing, but many don’t use data to diagnose their housing problem and evaluate the policies they put in place.

Angus Deaton perfectly characterizes the design of many housing policies when he writes,

"The need to do something tends to trump the need to understand what needs to be done. And without data, anyone who does anything is free to claim success."

Linking Income Distribution to Housing Consumption as a Diagnostic Tool

To design housing policy, you need to establish the minimum socially acceptable housing consumption level and the number of households who consume less housing than this level. By relating household housing consumption to income distribution, you can identify groups in need of help. Below is an example of a typical market with no intervention.

The top panel shows a typical consumption curve and the relationship between income and consumption (supply side). Consumption is best measured using a housing quality index that weighs different components like floor area, land area, access to transport, access to community facilities, etc. The curve ab shows the variations of housing quality under normal market conditions.

The bottom panel shows a typical income distribution and the relationship between income and the number of households (demand side). In this scenario, a household with income d will consume a quantity of housing g.

Impact of an Increase in Urban Land Supply

Before implementing housing policy, governments can improve affordability by removing supply side constraints. This could include slow building permits, height and density restrictions, minimum floor areas, barriers to urban expansion, or limits of construction technology. Through investment, alternatively, roads and infrastructure could be expanded to create more developable land.

The dashed line ac below shows the potential increase in housing consumption for all households when supply constraints are removed. In the long run every household benefits, but the size of the benefits is not the same for all income groups. Even with better functioning markets, governments will need to increase the housing consumption of the very poor after supply side reforms have been successfully implemented.

Demand Side Subsidies: Vouchers

Demand side subsidies help people looking for somewhere to live. Once an income qualification is set, the beneficiary can apply the subsidy to any home they want. Demand side subsidies, like vouchers, allow governments to support many households without a lot of additional bureaucracy.

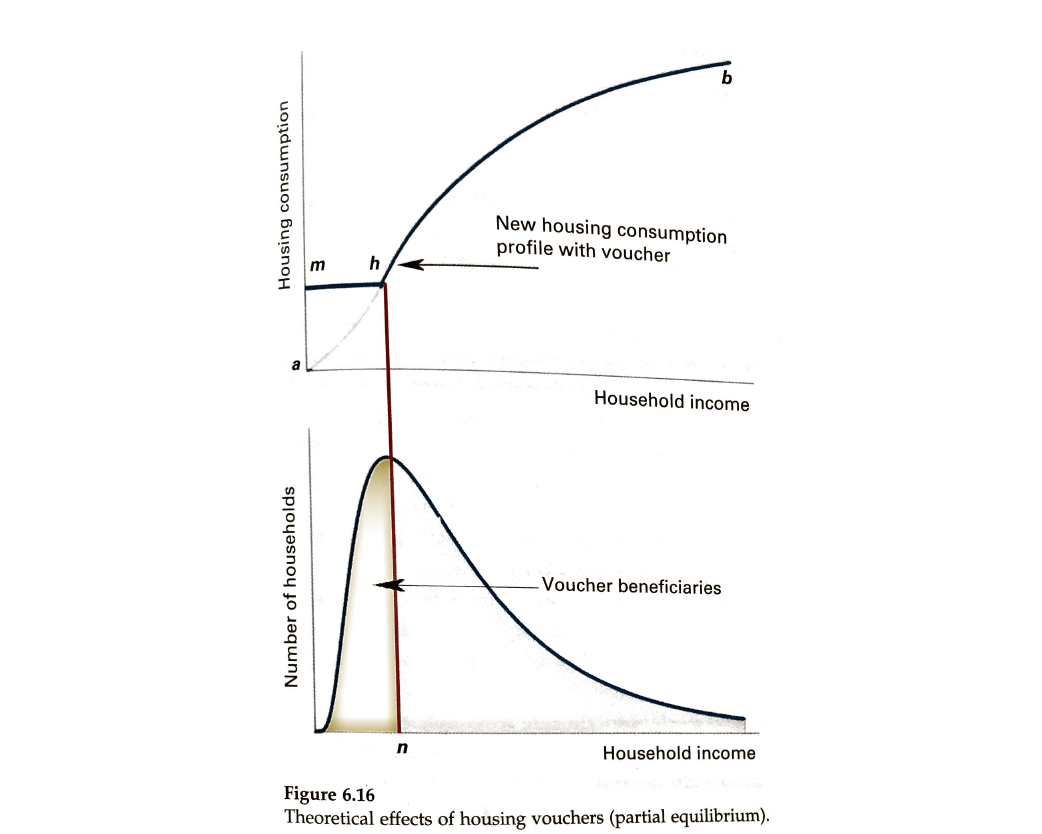

In this example, the government has decided two things: 1) minimum socially acceptable housing consumption = m and 2) every household whose income is below n would receive a voucher to allow consumption of at least m.

After all the vouchers are distributed, the new housing consumption curve is mhb. The cost to the government is the difference between line mh and curve ah. As income increases, the subsidy decreases making it efficient.

If vouchers aren't disbursed quickly, the program becomes a low odds lottery and creates false hope. Quick disbursement of vouchers is the goal, but it also creates demand. Housing supply needs to be able to respond quickly. There's no guarantee that developers can quickly deliver a large number of homes at the approved standard.

Governments should remove supply constraints before the subsidy. Otherwise, the additional purchasing power will create pent up demand and increase prices for all low income households and make a successful voucher program more costly.

Supply Side Subsidies: Public Housing

Supply side subsidies go to a developer to build a particular type of housing in a specific place for a set price. Qualified households must move to the unit that receives the subsidy, whose location and design have between selected for them by planners. Typically they must also stay in that unit to keep the subsidy.

In this case, a government has set up a public housing program. They've made all decisions about location, size, and design of the units to be rented to a selected target group. The total number of people eligible for the program is represented as a household with incomes between q and n below. The current consumption for these households varies from p to h on the consumption curve ab.

Households benefiting from the public housing are represented in red. The program could be expanded until the entire target population in blue lives in a public unit, but it would require enormous annual financial commitments and land supply.

Governments often build public housing to standards similar to market rate housing. The standards of this new public housing are between p1 and h1. These standards are significantly higher than the original standards of p to h of the target group. A potential problem is created when households in public housing end up with higher housing standards than households with higher incomes shown to the right of n.

Some beneficiaries are likely to cash in the potential rent by subletting their unit. Nearly all public housings regulation forbid subletting, but it's very hard to control informal subletting. Subletting shows that the beneficiary household would prefer the cash value of the subsidy rather than the value in-kind represented by the higher housing standard. The trade-offs made by the planner were different than the household.

Subletting also expands the number of potential beneficiary households of the new public housing. The informal extension reaches income n1 and the additional number of beneficiaries is represented as the shaded area above the income curve p1 to h1 + h1 to h2. This discourages private production of housing in this income range (n to n1).

Long bureaucratic processes along with funding and land requirements make it difficult for governments to deliver apartments for all the potential beneficiaries. For example, in Paris the current wait is 19 years if you divide the number of qualified applicants (243,000) by the number of yearly assignments (12,000).

Why Do Governments Often Prefer Supply Side Subsidies?

If the shortcomings of supply side subsidies are so evident and well documented, why do so many governments seem to prefer them to demand site subsidies? Bertaud believes that politicians like to cut ribbons in from of tangible brick and mortar project; they do not have this opportunity for demand side subsidies like vouchers.

In addition, in many countries the large bureaucracy in charge of building public housing is a reliable source of patronage jobs and contracts. The assignment of subsidized units to beneficiaries also becomes a source of patronage that politicians find difficult to resist.